Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as: ‘a category of cross-border investment in which an investor resident in one economy establishes a lasting interest in and a significant degree of influence over an enterprise resident in another economy.’

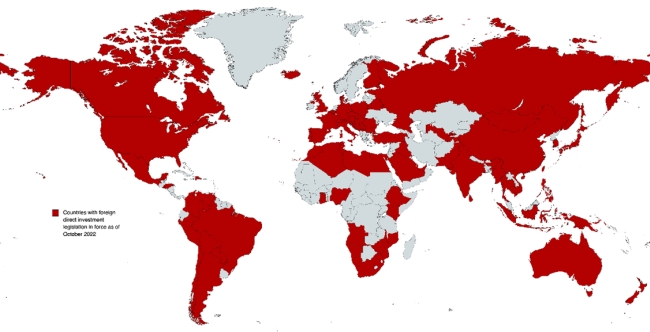

Over the last few years – and following the global COVID-19 pandemic – governments around the world have implemented FDI regimes to protect what they consider to be strategically important businesses from foreign acquisition or influence. An FDI regime offers a national government the ability to investigate and potentially block or impose conditions with respect to a proposed investment from (typically) foreign investors in companies operating in key sectors of the economy.

Historically, these sectors focused on key areas of national security, such as military and defence-related companies. However, driven in part by increased geopolitical threats elsewhere and developments in powerful technologies, the concept of national security now includes critical infrastructure – including energy networks and ports – communications assets, and advanced technology and data, such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and advanced encryption technologies and materials.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the relevance of a much wider range of businesses being directly related to matters of national security and public health, such as companies working on vaccines and personal protective equipment.

Against a backdrop of increasing global protectionism, FDI regulation has become a critical piece of the regulatory jigsaw in recent years, such that careful consideration must be given to the application of FDI rules to cross-border M&A from the outset, alongside merger control and other regulatory clearances. This can be the case even for acquisitions of minority interests as little as 1%.

While most investors are unlikely to be viewed as ‘problematic’, these regimes have significant implications for investors, particularly in terms of transaction timetables. Investors need to consider both their own position, but also that of any investment partners, and factor in these approval requirements into their acquisition strategies.